Many thanks for your letter of the 15th August and copy of acting cover. I detest that photograph because 1) I don’t believe it is a photograph of me at all, and 2) whoever the man is was floothered[2] when the picture was taken. I Feel any biographical material should be omitted, particularly the disclosure that Flann O’Brien is a pseudonym. There is no point in it if the real name is also given. Incidentally, if a pen-name is admissible, why not a pen-face?

Little did either of them realise that the individual elements required to bring Flann’s conjecture in that last sentence into being were already in place, although he would not live to see it come to pass...

For whatever reason, there are only a handful of good photographs of Flann O’Brien in existence, so you get to see the same ones turning up quite regularly. He’s usually pictured wearing a hat and an overcoat, sometimes with a wall, or a public house interior—or even a wall in the interior of a public house—somewhere in the background.

There’s one in particular that has in recent years appeared both on the cover of the Everyman’s Library edition of The Complete Novels[3] and the front cover of the first issue of The Journal of the International Flann O’Brien Society[4], aka The Parish Review[5], as well as sundry other places. It even features on a postcard as part of Penguin Books’ 100 Postcards from Penguin Modern Classics[6] box set, as well as in countless places online. And it’s easy to see why designers would choose it—it’s a black and white photograph of the top half of a relaxed, friendly-looking man, with the obligatory hat and overcoat, who has one hand up to the lower part of his face in a contemplative manner.

There are two things that mark this one out from the other photographs, though—for one thing, the subject is wearing glasses, which is not the case in any of the rest, and, for the other thing, the man in the photograph isn’t actually Flann O’Brien at all, despite all the above sources saying that it was.

This is how it all came to light: On Saturday 2 December 2017 the Irish Times published Professor Anthony Roche’s review of Flann O’Brien: Problems with Authority[7]. Accompanying the review was a photograph of three men sitting at adjacent tables, two on the left-hand side, and one on the right, which is subtitled as ‘Comic novelist and humorous columnist Flann O’Brien (right) in the Palace Bar in Dublin circa 1945. Photograph: Hulton Getty.’ The man on the right is not, as you might have surmised, Flann O’Brien[8]. The photograph was certainly taken in the Palace Bar, though, and is actually a companion to one mentioned above, and almost definitely taken at the same time.

Three days later, on Tuesday 5 December 2017, a letter appeared in the Irish Times that read,

Sir, – In a book review by Anthony Roche on a collection of essays concerning Flann O’Brien (Books, December 2nd), the caption on a photograph identifies the figure on the right as Flann O’Brien. This is in fact Robert Farren (1909-1984), poet, broadcaster and Abbey Theatre director. He was my father.

Hulton Getty has issued various versions of this photograph over the years with this misidentification; it appears in at least two British collections of Flann O’Brien’s works.

Apart from the fact that I recognise him, it is known—and your resident Flannorak, Frank McNally, will I’m sure confirm this—that Flann never wore glasses.

The figure lighting a cigarette in the photograph is the novelist Francis MacManus (1909-1965), an exact contemporary and close friend of my father. – Yours etc,

RONAN FARREN

The same photograph of the three men was published alongside the letter, this time re-subtitled as ‘The Palace Bar in Dublin circa 1945. The figure on the right is Robert Farren’...

The following week, on Thursday 14 December 2017, the self-same ‘resident Flannorak[9],’ Frank McNally, in his regular Irishman’s Diary column in the Irish Times, had written a piece called ‘The Phantom Flann—An Irishman’s Diary about the framing of Brian O’Nolan for a photograph he wasn’t in,’ and subtitled ‘O’Nolan spent his career pretending to be other people. And sometimes even the other people were not who they were supposed to be.’ An extract follows:

On behalf of Flann O’Brien fans everywhere, I offer belated thanks to Ronan Farren (Letters, December 5th) for solving a mystery that had perplexed our community.

For some time past, Flannoraks were aware of an ever-more-widely circulating photograph, supposedly of the man himself, from Dublin’s Palace Bar, circa 1945. It had even appeared on reprints of his books. But although the location was entirely plausible, as was the hat, the bespectacled figure was clearly not Flann.

My best guess was Niall Montgomery, his friend and collaborator, who did actually wear glasses. But I happily bow to the authority of our letter writer, who assures us the mystery man was his own father, Robert Farren, aka Roibéard Ó Faracháin, the poet. The file is hereby closed. Getty Images, please copy.

It is not without aptness, however, that the real-life Brian O’Nolan should have been supplanted in this way: even to the extent, eventually, that the picture accompanied the review of a new book about him in The Irish Times, the paper his other main pseudonym, Myles na gCopaleen, adorned for 26 years.

He of all people would have understood the existentially-threatening condition implied in a common Hiberno-English phrase: ‘He’s not himself lately’. O’Nolan spent his career pretending to be other people. And sometimes even the other people (eg Myles, often written by Montgomery[10]) were not who they were supposed to be.

Both photographs were still to be found on the Getty Images website shortly after all of this appeared, still tagged as being Flann O’Brien, but not long afterwards a search with his name in it yielded no results, nor does it to this day—he had been erased, and had become a sort of Orwellian unperson, a situation that Dermot Trellis in At Swim-Two-Birds might have sympathised with, if it wasn’t for the fact that he had been erased himself.

Now, there’s nothing I love more than a mystery, and the more intractable it is, the more I like it. As far as I could see, there were several questions that I wanted answers to—various variations on those old what, where, when, why, and who kinds of questions. Who took the photographs, and when and where did they take them, and for what reason? Why did they end up on the Getty Images site, and how did they end up being misidentified as Flann O’Brien? And who was the mysterious third man in that group shot?[11] There was digging to be done, so I started with what I definitely had: that photograph.

According to the information on the reverse of the Penguin Books postcard, the photograph is © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/Corbis[12], whereas the inside front flap of the dustjacket on the Everyman’s Library book says that it’s © Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images. And, as indicated above, the Irish Times had subtitled the picture as Photograph: Hulton Getty. There were several names attached to the photograph, and I’d need to find a concrete starting point for all this to help me make some sort of sense of what had happened, like why there were so many different names, for a start. In cases like this the Internet is our friend, and the much-maligned Wikipedia is always a good starting point. So...

The most recent iteration of the various related corporate entities whose names are attached to that photograph is gettyimages.com, the online presence of Getty Images, Inc, whose headquarters are in Seattle, Washington, having originally being founded as Getty Investments LLC in London in 1995[13]. Essentially, they buy up older photo agencies and archives and digitize their collections, thereby enabling worldwide online distribution. In 1996 they bought the Hulton Picture Collection for 8.6 million pounds, which gave them the rights to some fifteen million photographs from the British press archives, dating back to the 19th century. Getty bought this collection from Brian Deutsch, where it was originally called the Hulton-Deutsch collection. Deutsch had, in turn, bought the collection from the BBC, who had bought it in 1957 from Sir Edward Hulton, who had set up the Hulton Press Library in 1945 as a semi-independent operation to manage the growing photographic archive of Picture Post, a British photojournalistic magazine published by the Hulton Press from 1938 to 1957.

Once the magazine folded Hulton apparently lost interest, as he sold the archive—a move that, in 21st century hindsight, was perhaps not as financially astute as he might have thought. Still, with Picture Post we have arrived as far back as we can go, and exactly where we need to be, as it turns out[14]. And we have managed to touch base with every single corporate name under which that photograph was attributed—Getty Images, Hulton Archive, Hulton-Deutsch Collection, Hulton Getty, and Picture Post—except Corbis, about whom I’m just going to quote a large chunk of text from Wikipedia, because it’s just too bewildering for me to try to succinctly synopsise, as I write this, so you may read it or not, as you please:

[Corbis] was founded in Seattle by

Bill Gates in 1989 as Interactive Home Systems, and later renamed Corbis. The

company's original goal was to license and digitize artwork and other historic

images for the prospective concept of digital frames. In 1997, Corbis changed

its business model to focus on licensing the imagery and footage in its

collection. [...] In January 2016 Corbis announced that it had sold its image

licensing businesses to Unity Glory International, an affiliate of Visual China

Group. VCG licensed the images to Corbis's historic rival, Getty Images, outside

China.

So now you know—although we’re strayed very far from our original starting point. None the less, the date of some sort of semi-amalgamation with Getty in 2016 doesn’t quite explain their name being on the back of that Penguin Books postcard, as that dates from 2011. But there’s only so far we can go chasing down rabbit holes that are also potentially cul-de-sacs, so that’s as far as I’m going on this particular one.

Was any of this relevant, though? Well, yes, I thought it was. The two photographs, especially the one of Robert Farren, lovely and all as they were, were obviously professionally taken photographs, rather than simply the product of happenstance. The attribution of the photograph as having been taken in 1945, whilst it would prove to be wrong, was nonetheless at least a pointer in the right direction, and the fact that the date coincided with the establishment of the Hulton Press Library in the same year might not be entirely a coincidence, but simply a misattribution based on someone presuming that one date was the same as the other—although we’ll never know for sure. And, by now, I was sure that that this was all converging on the fact that those photographs had featured in Picture Post around that time. Everything seemed to point towards that—that they were almost definitely professionally taken, that they had been on the Getty Images site, and that one of the founding blocks of that collection had been the photographs from the Hulton Press Library, itself the archive of Picture Post’s photographs. And the attribution on the back of the postcard had even specifically mentioned the magazine. So all I had to do was to figure out how to prove that...

My next stop was the website of the National Library of Ireland. They had just one issue of Picture Post in their catalogue[15], it looked like, dated 11 April 1942. Could this be the one I was looking for? It certainly looked like it might be[16]. There was a feature in it called ‘In Eire To-Day,’ which was also the subtitle the issue was catalogued under. I no longer live in Dublin, but a week-long visit there to go buy books at the annual Trinity College Booksale meant I could easily go around the corner to the NLI and have a look at it for myself. And that’s exactly what I did. But, before I went, I would still occasionally put various possible search terms into Google, to see if I could find some combination that would throw out a viable result.

I wish I could remember what specific terms I used that night—it is likely to have been as simple as ‘Robert Farren’ & ‘Palace Bar’—but the very first result returned was for the Getty Images website, for an entry tagged with the date 11 April 1942, a date I had seen only a short while before on the NLI website. It is absolutely true to say that the hairs on the back of my neck, at least proverbially, stood up. I had, finally, found what I was looking for. The truncated Google search result (with my putative search terms highlighted in bold, as it would have looked) read,

...www.gettyimages.com › detail › news-photo > irish-wri...

Irish writer, broadcaster and Abbey Theatre director, Robert...

... Abbey Theatre director, Robert Farren at the Palace Bar in Dublin, April 1942. Original publication: Picture Post - 835 - Abbey Theatre - pub 11th April 1942.

Clicking through the link brought me to a page on the Getty Images site with that familiar photograph of Robert Farren, but now with text saying,

Robert Farren

Irish writer, broadcaster and Abbey Theatre director, Robert Farren (1909 - 1984) at the Palace Bar in Dublin, April 1942. Original publication: Picture Post - 835 - Abbey Theatre - pub 11th April 1942. (Photo by Haywood Magee/Picture Post/Hulton Archive/Getty Images)

It even had the photographer’s name listed. Most importantly, it stated quite clearly that the image had appeared in a particular issue of the Picture Post, and that issue of Picture Post was equally clearly listed on the National Library of Ireland’s online catalogue. And, as I said, I was going to be in Dublin within a few days, and would have an actual copy of the very issue of Picture Post that had that photograph of Robert Farren in it put into my own trembling hands. This part of the mystery, at least, was solved. Except that it wasn’t...

* * * * *

The 2020 TCD Secondhand Booksale took place in the Exam Hall in Trinity College’s Front Square from Tuesday 18 to Thursday 20 February 2020. On one of those days I was also going for a stroll up to the National Library of Ireland, which was at most five minutes away, and my precious documentary proof would be there waiting for me. I entered through the tiled and pillared rotunda of the entrance hall, bade a good day to the security guard on duty, deposited everything except an iPad Mini, a pencil, and a note book in one of those ‘set your own secret combination on the lock’ glass lockers, and ascended the marble and stone staircase which so many other great intellects had ascended before me, presented myself at the front desk in the main reading room, and asked the librarian behind the desk to supply to me forthwith my issue of Picture Post. He pointed out that there were actually two different issues of the magazine on the catalogue, and not just a generic listing indicating they had a copy or copies of Picture Post, and then a specific listing for the actual issue they had provided a date for, which was what I had convinced myself I was looking at, that first time I had looked it up in their catalogue. None the less, I had the date I was looking for to hand, and they did actually have that issue so, after having gone off for a pot of tea in the excellent Café Joly on the ground floor whilst it was being retrieved from the archives, I returned shortly thereafter and, finally, I was given their copy of Picture Post #835 published on 11 April 1942. I was, at least on the inside, incandescent with excitement.

I sat down at my desk, put the magazine down on the support cushion, and turned the first page. The first few pages were almost all advertising, as was the fashion at the time, except for some remarkably jingoistic readers’ letters on page 3—somewhat understandable in light of the war, I suppose—and a contents list on page 5. The promise of the front page, with its IN EIRE TO-DAY strapline was certainly fulfilled by the contents listed: An article by Cyril Connolly called ‘Neutral Eire is Slowly Changing Under the Impact of the World’s War’ runs through the whole thing, taking in photo features like ‘Eire, Land of Talk,’ ‘Dominant Influence in Eire is the Catholic Church,’ Can Eire Defend Herself?,’ and ‘In the Abbey Theatre,’ all of which took up pages 7 to 15. Somewhere amongst all that, surely, I would find a photograph of Robert Farren, and maybe even a previously undocumented image of Flann himself?

I turned the page once more. And I kept turning pages, until I got, not only to the end of those pages that covered the Irish content, but to the very back page of the magazine itself. And not one of those pages contained a photograph of either Robert Farren or Flann O’Brien. I was sure I must have missed a photograph, or somehow turned two pages at the same time, or in some other way overlooked the very thing I was looking for. So I went back to the start, and checked everything—the date, the issue number, and then scrutinised anew every single photograph on every single page, making sure as I did so that I was checking every consecutive page number, just in case. But to no further avail. That photograph, which was originally said to be Flann O’Brien, but wasn’t, was also not in the issue of Picture Post I was told it was in. The very magazine that had been the bedrock of what became Getty Images had deceived me not once, but twice, with the same image. What on earth was going on?

I did the only thing possible, which was go through it all again, even more carefully. The thing is, there were photographs taken in the Palace Bar, in the ‘Eire, Land of Talk’ section, and of the Abbey Theatre, accompanying the ‘In the Abbey Theatre’ section, obviously enough. There’s a photograph of legendary Irish Times editor RM Smyllie in his office, another of him in the Palace Bar, along with journalists Alec Newman and MJ McManus, and one further picture from the Palace, showing a person identified as ‘Pierce Beasley’[17] talking to artist Desmond Rushton. And the photographs of the Abbey show both an interior and an exterior of the original building, with the useful information that it had once been a morgue. There’s a photograph of a scene of a pub fight[18] from Seán O'Casey’s The Plough and the Stars, and half a dozen head shots of actors, and one more photograph of an Abbey Theatre producer. But none of these people were who I was looking for.

I conceded defeat, handed the copy of Picture Post back to the person behind the counter, and went back to the Booksale, and eventually back home, unsure of what had actually just happened. However, I was not without either resources or further plans.

I decided the possibility existed that there might have been different versions of the individual issues of Picture Post. After all, there were local editions of papers like the Sunday Dispatch, which would publish Myles na gCopaleen’s Column Bawn column in the early 1950s in their Irish edition, so maybe there had been different local editions of Picture Post for different markets? I’ll tell you now that this wasn’t true, especially seeing as this was during the war years, when such extravagances weren’t exactly welcomed. None the less, it did lead me to buying myself a copy of the 11 April 1942 edition of Picture Post, just to see. But the contents of that were exactly the same as the one I’d already looked at, of course—although it did mean I had a chance to do more than just have a look through it in the library.

There was that other Irish-themed copy of Picture Post, though. The one I’d originally overlooked on the NLI online catalogue. I bought a copy of that, too, just in case. But it was a complete non-starter, for lots of reasons. If nothing else it dated from almost two years earlier, 27 July 1940, which meant it pre-dated the first Myles na gCopaleen penned Cruiskeen Lawn column in the Irish Times by nearly three months. And most of the Irish contents in that particular issue was about showing how poor we all were, it looked like. So that particular cul de sac was entirely cut off.

As a last resort, and seeing as I actually had access to me own copy, I set myself to reading Cyril Connolly’s essay in the April 1942 issue. It would be fair to say that it was at the very least condescending, and often substantially worse than that, and there were quite a few ‘Oh do you fucking think so?’ moments, as I read through it. But, near the end, I found this:

Culture itself struggles on, not

really taking that advantage of being out of the war which culture should, but

represented by some interesting young poets and writers. There is Robert

O’Farocháin, a gifted young poet, Francis MacManus, a novelist, Flann O’Brien

(a Gaelic Beachcomer), Donagh McDonagh, a poet whose father was executed in

1916, and the story writer, Niall Sheridan.

At last I had found at least a tenuous link between that photograph, originally thought to be Flann O’Brien, but later revealed to be Robert Farren, aka Roibeárd Ó Faracháin[19], and the 11 April 1942 edition of Picture Post. Was there any way to explain why the photograph wasn’t in that issue, though, even though it was listed on the Getty Images website as having been so? Maybe there was.

In the Wikipedia article about Picture Post there’s this paragraph, with bold emphasis added by myself:

As the photographic archive of Picture Post expanded through the Second

World War, it became clear that its vast collection of photographs and

negatives, both published and

unpublished, were becoming an important historical documentary resource.

So, if there had been a batch of photographs taken in the Palace Bar by their stringer photographer, Haywood Magee, which were for that issue, it would be reasonably that some would be used, and some not. And the unpublished ones would probably be in the Hulton archive alongside the published ones. Somewhere along the line, possibly when they were being digitised for the website, or possibly well before that, someone made a partially educated guess about who was who, going on the above paragraph from Cyril Connolly’s essay, and decided that the nice man in the black hat looked a bit like the only one of that group that there were a handful of photographs of to provide any sort of comparison, and tagged it as Flann O’Brien, and further presumed that, if the photographs were taken for that issue, then they must have been in that issue, and all the pieces fit together at last. The secret origin of Flann’s Pen-Face was revealed at last.

There were still a few loose ends that needed tying up, but I think I can provide answers for those as well. Who was the third man in the photograph that contains Robert Farren and Francis MacManus?

It’s likely that he was one of the five young writers listed together— Robert Farren, Francis MacManus, Flann O’Brien, Donagh McDonagh, and Niall Sheridan. The first two are already in the photograph, it’s definitely not Flann, so it’s down to Donagh McDonagh and Niall Sheridan. From various online photographs of McDonagh I’m pretty sure it cannot be him, so that pretty much leaves Niall Sheridan. And there’s a certain resemblance between that third man and a grainy old photograph of him from the Irish Times. Perhaps somebody in the know will read this, and can confirm or deny that. And, if it is indeed Niall Sheridan, then Flann might not be in the picture, but at least one of the occasional (but not often) substitute Myles na gCopaleens is.

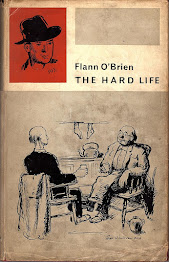

The one other thing, to go right back to where I started out, is the business of Flann’s letter to Timothy O’Keeffe of 19 August 1961, about the cover art for his forthcoming novel The Hard Life, where he said,

Many thanks for your letter of the 15th August and copy of acting cover. I detest that photograph because 1) I don’t believe it is a photograph of me at all, and 2) whoever the man is was floothered when the picture was taken.

I Feel any biographical material should be omitted, particularly the disclosure that Flann O’Brien is a pseudonym. There is no point in it if the real name is also given. Incidentally, if a pen-name is admissible, why not a pen-face?

The thing is—and this is very much the leitmotif for this essay—that cover for MacGibbon & Kee’s original 1961 publication of The Hard Life has no photograph, whether of Flann or anyone else, anywhere on the dustjacket. Nor is there any biographical material, and therefore no disclosure of the author’s name being a pseudonym. But this particular mystery at least has a more easily found possible solution—none of the things Flann objects to in that letter are in the UK first edition, but every part of it is to be found on the inside back flap of the dustjacket of the American first edition, published by Pantheon Books of New York in 1962. This is what it says:

Flann O’Brien was born in County Donegal a few years before the First World War. In 1943 Time wrote: “On one Irish matter there is no argument in all Eire: the favorite Irish newspaper columnist is Brian O’Nolan, who write for the Irish Times....O’Nolan, a novelist, playwright and civil servant, writes a six-a-week column titled Cruiskeen Lawn (The Little Overflowing Jug) under the pseudonym Myles na gCopaleen (means Myles of the Little Horses)....” Since then, Flann O’Brien has let down none of his three personalities: he has continued to be Ireland’s favorite spoofer and iconoclast in the Irish Times; he has been Secretary to three successive Ministers in the Irish Local Government and is Principal Officer of the Town Planning section; he has written several plays in Gaelic and has seen the extraordinary first novel that he wrote in his youth, At Swim-Two-Birds (Pantheon, 1951), rhapsodically acclaimed in England when it was reissued there last year. The Hard Life, written in a completely different style from that of his first, Joycean novel, represents the fourth dimension of this versatile writer.[20]

And the article was topped by a photograph. The photograph, unlike much of the information in that paragraph, dates from the same time as the book and, although there is no doubt that the man in it does indeed look floothered, there is no doubt that it is Brian Nolan himself, only a few years before his untimely death in 1966. Sic Transit Gloria Mundi, as he might have put it himself.

[1] The Hard Life, Flann O’Brien, MacGibbon & Kee, London, 1961;

Pantheon Books, New York, 1962

[2] Maebh Long, in her excellent The Collected Letters of Flann O’Brien

(Dalkey Archive Press, Dublin, 2018) added a footnote to this, saying that it

was an Irish colloquialism meaning drunk. I can offer no further or better

explanation.

[3] The Complete Novels, Flann O’Brien, Everyman’s Library/Random

House, London, 2007

[4] Now known as the Journal of Flann O'Brien Studies.

[5] The Parish Review #1, International Flann O’Brien Society, Vienna,

2012

[6] 100 Postcards from Penguin Modern Classics, Penguin Books, London,

2011

[7] Flann O’Brien: Problems with Authority, Ed. Ruben Borg, Paul Fagan,

& John McCourt, Cork University Press, Cork, 2017

[8] Nor was the photograph taken in

1945, but I’ll be coming to that later on.

[9] Although some of us prefer

Flanneur.

[10] I take issue with the use of the

word ‘often’ here, but that is very much an argument for another day, and one

that Frank McNally is not entirely unfamiliar with upon my part. Research, as

ever, is ongoing.

[11] Was he by any chance a policeman,

and did he have a bicycle? No, probably not.

[12] I have a few copies of that postcard—although it originally came as part of a set of 100 postcards some sellers, both in the actual and virtual marketplaces, break up these sets, and sell the postcards individually—you can buy the entire box online for something like €15, so even selling them for a mere £/$/€1 each, there’s plenty of profit to be made. I have it on good authority that, certainly at the time the inadvertent imposture came to hand, that Penguin UK had about 2,000 boxes still to hand. Anyway, I like to have a few to hand to send to people, particularly since I found out about the inadvertent imposture on the sitter’s part.

[13] The Getty in Getty Images is

Italian-born Mark Getty, who holds an Irish passport, and is the grandson of

John Paul Getty, the oil tycoon, once reckoned to be the richest private

citizen in the world, and notorious for his penny-pinching ways. Still, he’s

dead now, for all the good it did him, and sure there’s no pockets in shrouds.

[14] To synopsise the foregoing

paragraph: Sir Edward Hulton set up the Hulton Press Library in 1945, which he

sold to the BBC is 1957, who sold it to Brian Deutsch in 1988, who then sold it

to Getty Images in 1996. Who, at the time of writing, appear to still own it.

[15] There’s actually two, but I didn’t

notice that the first time I looked. And there’ll be more about that a little

further on, anyway.

[16] There

had been an article by Allen Barra in the Wall

Street Journal on 17 March 2011 (aka Saint Patrick’s Day) entitled ‘Flann

O'Brien—Tall Tales, Long Drink,’ which was accompanied by the now-familiar

photograph, subtitled ‘The

author/columnist at the Palace Bar in Dublin, 1942.’ So this date was

looking possible, as well.

[17] He was born Percy Beazley, but

later used a gaelicised version of his name, Piaras Béaslaí, so misattributed

here, regardless of which language you’re talking about. Piaras Béaslaí wrote

an Irish language science fiction novel called Astronár, which I’m looking for a copy of. If you have one, get in

touch!

[18] Presumably on the basis that, if

you can’t get a good pub fight in an Irish pub, then one on the stage of the

Abbey Theatre is probably the next best thing.

[19] So, once again, with Robert

O’Farocháin, Picture Post had failed

to get an Irish writer’s name right, in either language...

[20]

It’s amazing how many errors, mistakes, and out-of-date material you can get

into one paragraph, all the same, isn’t it?